Childhood Cancer Series: Unveiling the Survival Divide

Imagine walking into a hospital in the U.S.

Typically, when you walk through the doors, an overly clean and sterile smell will flood your nostrils. The floors are usually so clean and white you can see your own reflection, and it’s completely enclosed with central AC. It’s rarely overly hot or cold, and there’s a hand sanitizer dispenser every few feet. All of these elements in our hospitals help prevent the spread of disease and cross-contamination and provide an environment for patients to feel safe and comfortable in order to get better.

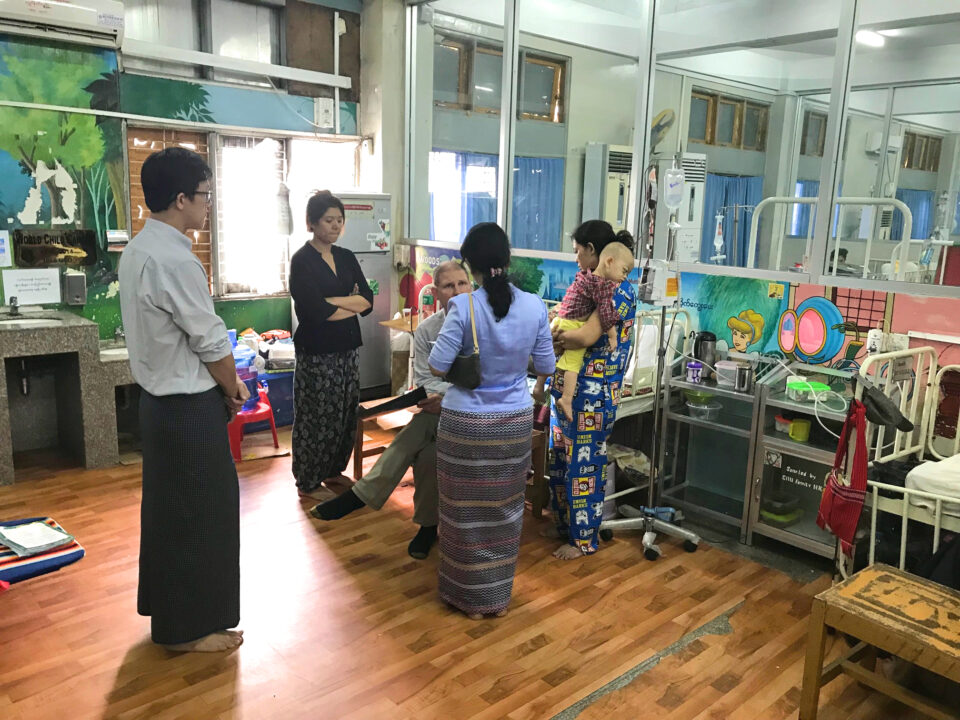

For the third installment of the Childhood Cancer Series, we will begin at a hospital in Yangon. Dr. John van Doorninck, a Pediatric Oncologist at Rocky Mountain Hospital for Children in Denver and the Chair of the World Child Cancer Global Program Committee, and his wife, Dana Bryson, the Board Chair of World Child Cancer USA (WCC), traveled to Yangon in 2019 and saw first-hand how childhood cancer impacts the low-income country of Myanmar in Southeast Asia.

In Yangon, the hospital was very different from the big city hospitals in America that we’re used to. Bryson describes the hospital in Yangon as an “inside-outside” building. The windows were open and had no screens, which was letting in the outside air and insects. They resorted to this measure due to the absence of climate control, which restricted their ability to shield against extreme heat, rain, and cold temperatures.

Another part of the hospital that caught their attention was a hand-washing station. As we know, washing our hands prevents the spread of infection and disease and is one of the easiest ways to keep us healthy.

“[In Yangon], it’s not the type of hygiene and sanitary standards that we would be used to,” Bryson recalls.

This was the only spot for families who came in from outside to wash their hands.

“Sometimes, simple, inexpensive interventions can be a first step to improving outcomes in a hospital. Handwashing is one such method that is data-proven to decrease rates of hospital-transmitted infection,” Dr. van Doorninck says. “For this reason, World Child Cancer installed a hand washing station to decrease the risk of infection in their immunocompromised patients.”

Bryson adds that the WCC saw this as a way to help families and the medical staff improve sanitary conditions for families who came to visit their children.

Statistical Difference

As mentioned in the first part of the Childhood Cancer Series: Treatment Advancements, there have been tremendous childhood cancer treatment advancements in the U.S.

“Childhood cancer, in general, has been one of the success stories of modern medicine in the last half-century in high-income countries,” Dr. van Doorninck says. “Where survival rates went from really negligible in the 50s and 60s to upwards of 80 percent here [in the U.S.]. In aggregate, in the low and middle-income countries, their survival is about 20 percent.”

Similarly to the U.S., other developed countries share a similar survival rate statistic. Unfortunately, less privileged countries have been left behind in these treatment advancements.

Why Are Underdeveloped Countries Struggling?

The gap between First, Second, and Third World countries is significant, and several reasons contribute to this disparity.

No Diagnosis/Late Diagnosis

Globally, 225,000 children are diagnosed with this disease.

“An estimated 400,000 children around the world develop cancer each year, only half of whom are ever diagnosed,” states St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

It’s estimated that 175,000 children in low- to middle-income countries are not even making it to a hospital to get diagnosed. One reason families aren’t making it to the hospital to receive a diagnosis is transportation issues.

“When we were in Yangon, we spoke with a family who traveled nine hours on three buses, and they slept in the parking lot outside of the hospital,” says Bryson. “Literally, there were blue tarps tied to sticks in an old parking lot outside the hospital, and that’s where they were cooking with an open fire.”

A family who has to pack their belongings and travel from a rural village to a big city to seek help is unheard of in the U.S. The ease of jumping in a car, using a Ride-Share app, or calling an ambulance is not something everyone has the privilege of using.

Because it’s difficult for families to get to the hospital, many children are receiving a late diagnosis and present with late-term cancer, which is more challenging to treat.

Limited Capabilities and Resources at the Hospital

From receiving the surgery and looking at a tumor under a microscope to making a diagnosis, many countries do not have the necessary resources or capabilities to make these types of diagnoses or treat the disease.

“If and when an appropriate diagnosis is made, there are challenges with delivering treatments, be that chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy,” Dr. van Doorninck says. “If that treatment is given, there are challenges with supportive services. One example is chemotherapy administration, which often results in the need for blood transfusions. However, there can be limited access to this type of supportive care in resource-limited areas.”

Medical training in the U.S. and health care standards are significantly different than in lower-income countries. Because of resource constraints and a less experienced medical team, the critical care necessary for the survival of these children is not being provided.

Families’ Lack of Necessities

As well as hospitals having limited resources to treat these patients, families also struggle with basic necessities like food. Dr. van Doorninck explains that nutrition is strongly linked to positive outcomes in childhood cancer, which can impact the signs, symptoms, and a child’s overall health.

Bryson adds, “One hundred percent of the kids in the facility [in Yangon] that we spent a couple of days visiting did not have appropriate nutrition. That included the children with cancer and their siblings.”

It’s not as common in the U.S. to have families and children going hungry and having health problems due to malnutrition. Moreover, families have a limited ability to pay for the treatment, which can impact their child receiving the treatment they need.

“All of these things can add up to what we call abandonment of treatment, which is almost unheard of in this country [U.S],” Dr. van Doorninck says. “But there are some patients that would present for diagnosis. Once the diagnosis is made and the treatment plan is given, the patients may not return to have a follow-up for their treatment, either because they have limited ability to pay, transportation issues, or because they have to make very difficult choices between their one child who’s sick and others who need their attention and resources at home.”

What is Being Done to Help these Countries?

Certain groups and organizations are trying to help these countries where children aren’t receiving the support they need. For example, the WCC is working towards a goal where every child has equal access to treatment and care.

“At World Child Cancer, we’re working to close the survival gap between low- and high-income countries and make sure no child suffers,” says Bryson. “We work a lot with training medical providers, nurses, and other traditional healers, so if there’s even a sense that your child is not eating or has lost 30 percent of their body weight or something like that, there’s a sense to ask that question.”

From the lack of basic resources to hospitals being unable to provide the vital care these children need, this disparity between low- to middle-income and high-income countries is a multi-layered issue. To help these children and their families, people can raise awareness about this issue, donate to WCC, attend an event, or involve your company’s workforce.

Many children who go through chemotherapy will lose their hair, so the WCC organization has partnered with Love Your Melon (a hat company), which donates hats to help these children.

“Worldwide, we need to do a better job of making the treatments available here, available to those who are in more economically challenged circumstances,” Dr. van Doorninck says.